‘Those who can, do; those who can’t,

teach’

(George Bernard Shaw, ‘Man and Superman’, 1905)

‘Those who can't do, teach. And those who can't teach, teach gym.’

(Woody Allen, Annie Hall, 1977)

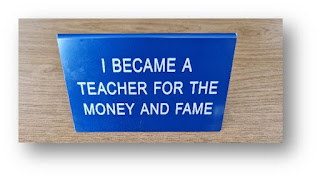

A few years

ago, my youngest two daughters went to New York on a sightseeing trip. Neither had been before and they had a wonderful

time together. They brought me some souvenirs,

one of which sits on my work desk and makes me smile every time I glance at it.

It’s a desk

plate displaying the following legend:

Any

fellow teachers out there (and presumably non-educationalists too) will

appreciate the irony of the quotation.

For if that were really the case, many of my colleagues and friends

would not be standing on the picket-lines losing a day’s pay to make their

point. If anything, carrying out our

jobs leads to infamy! I didn’t become a

teacher to curry favour with students. I

chose this profession because I believed, and still do, in the intrinsic

importance of education in a young person’s emotional and intellectual

development. Teaching adolescents is

highly rewarding whilst simultaneously managing to be frustrating, exhausting

and at times soul-destroying. Why do I

put myself through this on a daily basis?

That is a question I have been asking for over a decade? Because I wouldn’t dream of doing anything

else.

Topics include

the laws regarding the treatment of a Hebrew slave (also known as an ‘indentured

servant’); the granting of loans; the rules regarding setting up courts of law;

the observance of the festivals; separating meat and milk and the mistreatment of

foreigners.

The Hertz

Chumash uses the following useful categories to help us make sense of the order:

1.

Civil Legislation.

2.

Personal Injuries.

3.

Offences Against Property.

4.

Moral Offences.

5.

The Sabbatical Year and the Sabbath Day.

6.

The Three Annual Pilgrim Festivals.

7.

Moses’ warning of what would happen if the laws weren’t

followed.

The laws that

Gd instructed our teacher Moshe, immediately following the giving of the Ten Commandments,

make up the bulk of the Parasha. If we place

these in the context of what has happened to date, they are remarkable. From the beginning of Bereishit until the end

of last week’s Parasha of Yitro, the style employed throughout the Torah has been

that of a narrative.

As Rabbi Sacks’

and others have pointed out, this is not accidental. The Torah’s function as a Holy Book is to educate

us. The word ‘Torah’ means ‘direction or

instruction’ from the root of yud-resh-hey (ירה) which originally meant ‘to throw or shoot

an arrow’ and in modern Hebrew refers to firing or shooting a gun. In its causative form, it means ‘to cause someone

or something to move straight or true’. Like

an arrow, the Torah gives us strong direction.

It tells us how to ‘fly correctly’ following a straight line. In other words, it guides us.

What’s the best way of educating our children (and others) to set them up on the ‘straight path’? By telling them stories. If I were to give you a choice of either reading a list of laws or hearing a story, which would you prefer? I know that if it were me, I’d definitely go with the latter option. Stories are fun. You can engage with them. You can relate, especially if they inform you of something that you didn’t know; all the more if they move you in the process.

However,

if the Torah was simply a storybook, would it have maintained its position as

the world’s best-selling tome? According

to the British and Foreign Bible Society, as of 2021, it is estimated that

between five and seven billion copies of the Christian Bible have been sold

and/or distributed. When you consider

that the earth has recently registered its eighth billionth human birth, this

means that the vast majority of us have a copy of the Bible, which of course

includes a translation of the Torah. How

accurate this is would be the subject matter of a very different Drasha.

If the Torah

were simply a storybook, our arrow may fly in a straight line, but it would not

reach its destination. It must be solidly

constructed and able to negotiate all kinds of obstacles in its path. The commandments are its housing. Stories are nice but, to be effective, they have

to carry a message.

Mishpatim

opens Gd’s gift by sharing its contents following the thunder, lightning, thick

cloud and the sound of the Shofar which terrified the people as they witnessed

the giving of the Torah. Just as I didn’t become a teacher for the ‘money and the

fame’, so the Torah, our textbook and then some, is much more than the spectacle

that we witnessed in the desert.

Moshe, our

teacher, gave us Gd’s curriculum which includes every subject under the sun, including

our annual timetable. We need to have a Parasha

like Mishpatim to take us beyond the stories, so that we can create societies based

on the moral guidance therein. Without the

mitzvot, the stories are empty. Without the

stories, it is difficult to envisage how to keep the mitzvot. We need to see living, breathing examples of people

learning from the Torah and ‘living it’.

That’s how we can benchmark their behaviour against our own. That’s how we can literally ‘live the Torah’.

Reading

the Torah elevates my soul. My choice to

lead a life as an Orthodox Jew leaves little in my

bank account, especially when it comes to keeping Kosher. That said, despite the huge amounts of money

I could have saved, I wouldn’t have chosen any other path to follow. Just like my decision to become a teacher.

If I have

managed to pass that message onto anyone else, I can be comforted in the knowledge

that my arrow has hit its target.

On a

final note, I’d like to refer to Woody Allen’s quote and how misguided I think

it is. Through the years, I can honestly

state that ‘those who teach gym’ are some of the best practitioners I’ve come

across in our profession. I would add

that those who can teach are some of the most important individuals

making up our society.

A thought

to leave you with.

Who was your

favourite teacher and why is this the case?

Are they

rich and famous?

Shavuah

Tov

No comments:

Post a Comment